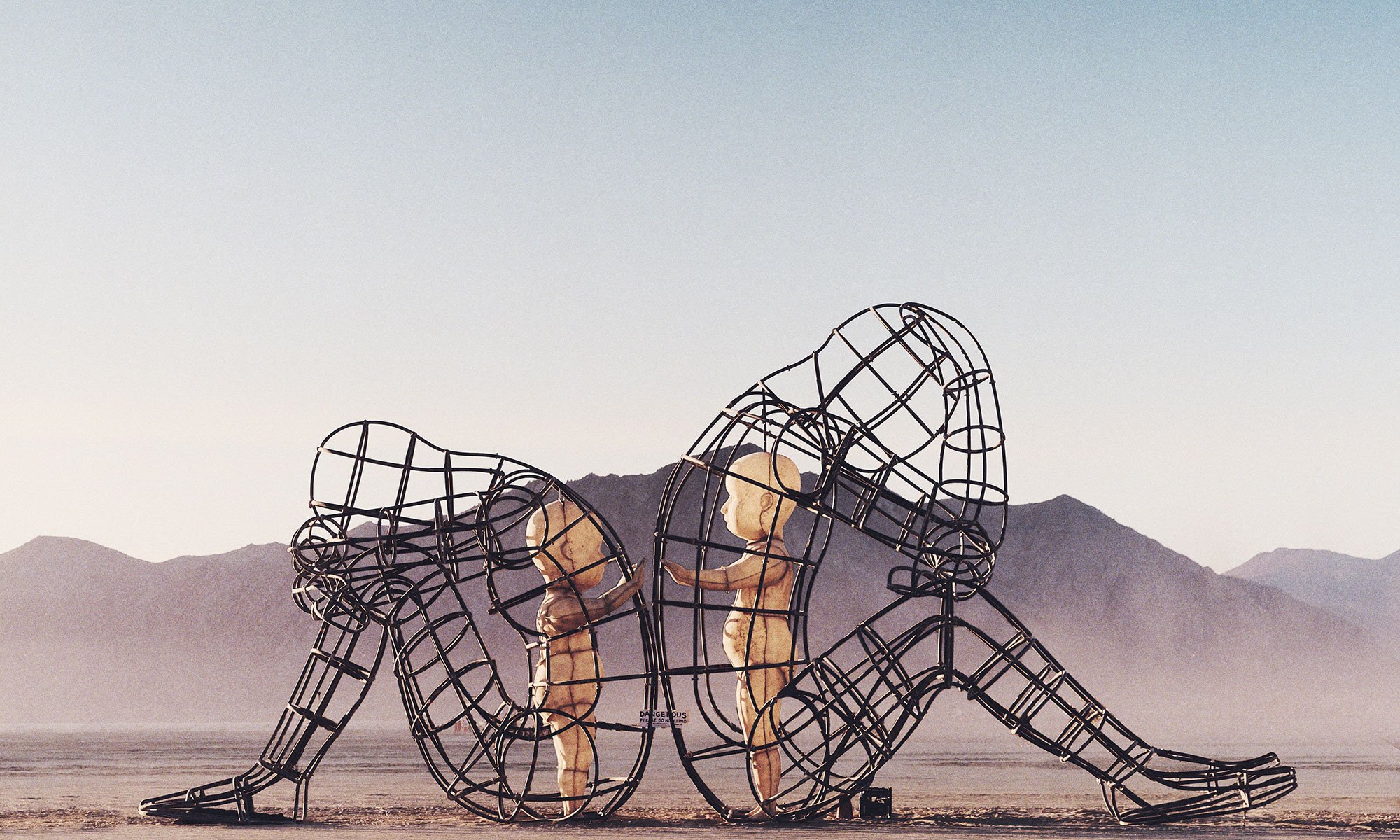

Humans are independent beings right from the beginning, not just in biological and medical terms, but also psychologically and socially. At the same time, they are social beings and their relationships, whose structuring begins long before birth, have very practical social and ideological consequences, which show up in how they deal with others, with themselves, with life. The basic philosophical and psychological assumptions about the world, society, life, existence itself, are unconsciously shaped by our experiences in the prenatal period of our life, which include the direct experiences of the foetus of itself and of external stimuli, vehicled through the mother, and the influence of the inherited information.

When life’s events generate fear of the future, investing the present and projecting backwards, on the past, creating thus a biography fit to measure, not of reality but of one’s personal emotions, the sentiments of solitude and abandonment accompany the individual throughout life’s journey and at every turn of the way memories are reformulated on the bases of expectations, with a retroactive effect which makes them ever-changing and shimmering, today stressing the dark shadows and tomorrow crying over the lost bright lights. This can be true of an individual, but also of an entire community when the community shares the experience of traumatic events and the archetypal psychological heritage.

Is it possible that man is organised around his past, of which he has lost consciousness? Is it possible that man depends on remote experiences of which he has lost consciousness? Is it possible that man finds himself living circularly historical courses of which he has lost consciousness? Starting from such a hypothesis, we can assume that man’s behavioural destiny depends on his “beliefs”; beliefs which are passed on and consolidated primarily through the hypothesis-hypothalamic maternal projections, which, in turn, have been influenced by the atavistic beliefs of her ancestors. A vicious circle void of any experimental proof but capable of producing stereotypes and beliefs based on the simple evidence of an event that has occurred, because humans feel secure only when the events are recognized through experience. Change, as Bion says, is catastrophically dangerous because it creates impotence of control. The result is that we can only repeat what has already happened because it is envisaged and recognisable: the new arises from the old and acceptable. We have, here, a dichotomic condition where the ego is confronted with the need to satisfy primary needs through the unconscious urge of centrifugal energy, which wants man to be expansive, proposing, cosmic and vertical, but also with the urge to obey the laws of the super-ego, which recognizes and selects the conscious and unconscious proposals. The attempt to find an acceptable compromise between a futuristic, or removed new-old event and the old and stale experiential classifier, represented by the super-ego, assembled by a retrograde system promoted by a parental-social regression, creates aggression and closure. The intrauterine phase of life appears as a unique occasion in which it is possible to intervene psycho-organically and interrupt this vicious circle of pathologically recidive retroactive dynamics.

Prenatal psychology is a relatively new interdisciplinary scientific field, dealing with the intra-uterine experience of the foetus and with the conscious and unconscious psychosocial dynamics that are generated by a pregnancy in its environment.

Just as the prenatal period is followed by birth, likewise every new phase in life, be it of individuals or of communities, can be considered as a birth to a new life and, just as the intra-uterine experience represents also a learning experience, every new phase in life has a prior preparatory learning phase. This is a vital phase because it is here, through conscious or unconscious memories, that we experiment and learn to adapt, creating thus an essential precondition for survival as individuals and as communities.

Today there is more and more evidence in support of the primacy of function over structure, according to which the morphological structure develops as a result of an inborn primal functional urge, but what generates the urge and how is it expressed in everyday life?

Knowing that any significant event will most certainly leave important traces, which will, in turn, influence future choices and events, people and the community at large tend to block out their wider understanding of events and to fix their interpretations of these events on narratives that focus on the particular episode. Although such fixed stories provide people with a certain meaning and identity that enable them to survive, they tend to be highly polarised, and, hence, they tend to undervalue (if not suppress completely) both the periods that preceded and, indeed, anticipated the significant events as well as the periods that followed these events. Accordingly, the phase when these events occurred seems to remain fossilised and it is this phase that tends to fix the meaning of everything else.

It appears that, just as morphological structure develops as a result of an inborn primal functional urge, human nature and behaviour develop as a result of human life and history; just as pregnancy, a period of preparation, can be conceived as an active dialogue between the child and the mother and, through her, also the father and the whole psychosocial environment of the mother, the period of a nation’s transition from one form of socio-political life to another, can also be conceived as an important evolutionary moment, in which a dialogue with a wider holding and nourishing international human environment is of fundamental importance and inestimable value as a mutual interdependent process.

Psychotherapeutic research and practice has shown how decisive negative emotional influences and disturbances in the prenatal dialogue can be on mental conditions and diseases later in life, likewise, negative and difficult social conditions in a transitional period of a nations’ evolution can generate roots of an even more instable and conflicting future, which can end up by involving the life of the whole planet.

Any living organism strives constantly to maintain its health and to keep away from illness and destruction; it strives towards homeostasis and away from disorganization; likewise, a community, a society, but the world can change only if we achieve a change in the basic understanding of respect for life from its very beginning, even before it is conceived.

The arrival of a baby, even if desired and loved, in a sense, represents a catastrophic event in respect to the former homeostasis, yet, it is an enrichment and, as Prof. Peter Fedor-Freybergh so nicely put it in his paper for the 13th International ISPPM Congress:

“If we can ensure that every child is loved and wanted from the very beginning, that it will be respected and that respect for life is placed highest on the scale of human values and if we optimize the prenatal and perinatal stages of life without frustration of basic needs, without aggression and psychotic influences, the result could be a non-violent society”.

Social upheavals are also catastrophic events, which, sadly, we see every day around the world. If we can do what Prof. Peter Fedor-Freybergh invites us to do, then we can ensure that on a social and even planetary level every individual and every nation is welcome and respected by the human community and that life is placed highest on the scale of human values and if we optimize the period of incubation and transition to a new society, avoiding the frustration of basic needs and avoiding aggression and, rather, empower the people with knowledge and confidence in themselves and in their fellow human beings, the result could be a more stable and non-violent world.